For many years I knew almost nothing about chemistry. I have a fairly good physics background, I know how atoms look like, the nucleus, electrons, orbitals, we even solved the quantum mechanical equations for hydrogen atom in college. But that’s all, I didn’t know anything beyond that. Recently I decided to fix that and read a very nice undergraduate textbook named Chemistry for the Biosciences. Here are my notes. All the visualizations and pictures are done in Wolfram Mathematica.

Atoms

The first chapter is about atoms. There is nucleus with protons (positive charge) and neutrons (no charge). Number of protons determines what element the atom is. Hydrogen has one proton, carbon has six, nitrogen has seven, oxygen has eight.

Every atom has a corresponding number of electrons orbiting around the nucleus. Electrons are negatively charged, are extremely light compared to the nucleus, and the number of protons and electrons is the same so that the atom as a whole has neutral charge.

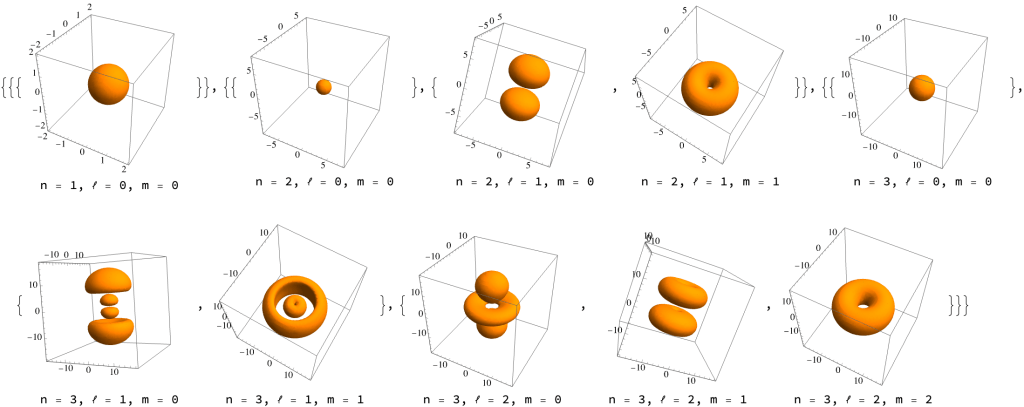

Electrons are orbiting not like planets, on elliptical trajectories, but in a weird quantum mechanical way. As the number of electrons grows, they are composed around the nucleus in “probability clouds” called orbitals. Here’s how they look like (plotted using the RegionPlot3D function, according to this Mathematica StackExchange answer).

The bigger and more complex the orbital is, the higher is the energy of the electron. And the asymmetrical orbitals have 3 copies along the x, y, and z axes. If you really want to understand this, they are solutions of the Schrödinger equation for hydrogen atom. The Feynman Lectures on Physics have a chapter on that. It’s volume III chapter 19, at the very end. Not easy.

Covalent bonds

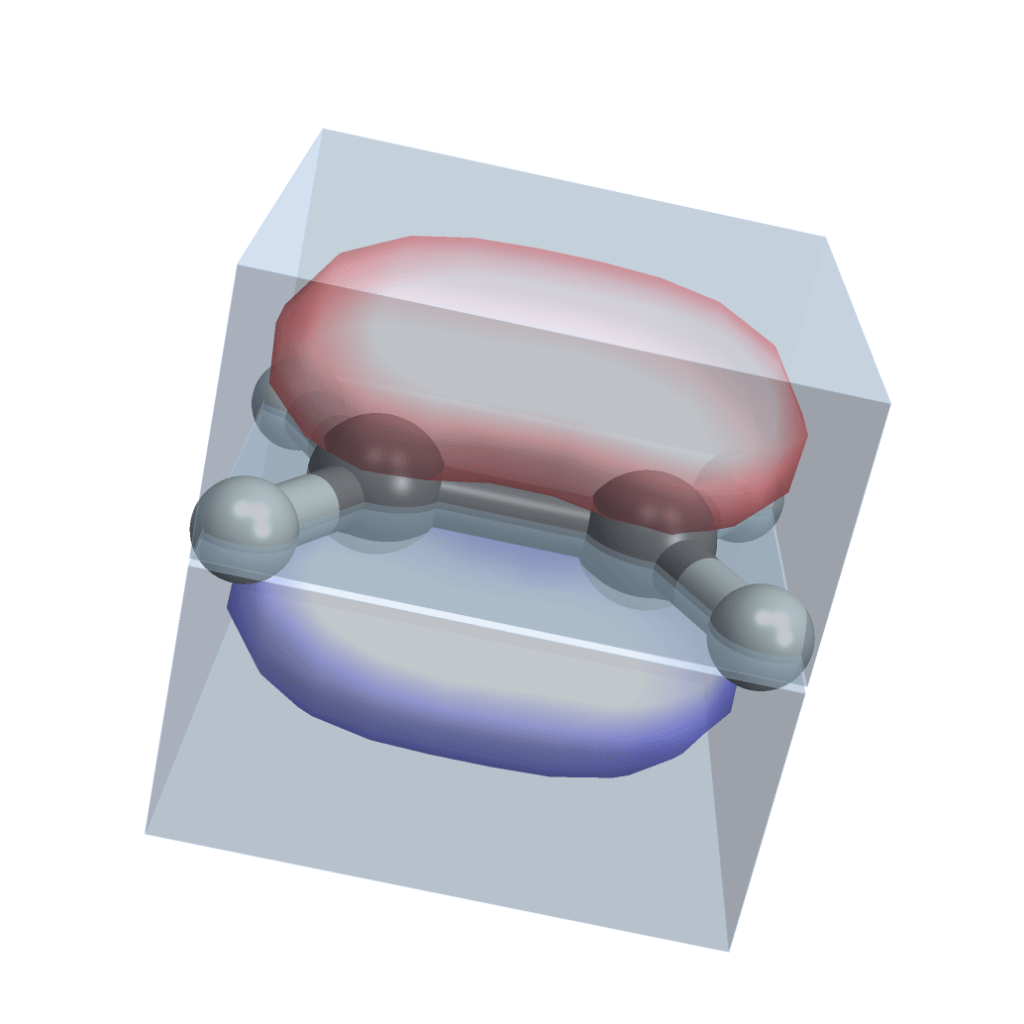

Most atoms don’t want to be alone. Only the noble gases do. Turns out they are more stable if they share electrons. Each nucleus has no longer its own set of orbital clouds, but some of the clouds merge together. Look at this molecule of ethene (two carbons and four hydrogens) and note how the two carbons share electrons in a common prolonged orbital cloud (I used this Wolfram Demonstration Project, it has examples of several other molecules):

This sharing of electrons is called a covalent bond and it’s what holds everything together. There is a tremendous amount of details that you can know about covalent bonds. Different elements have different numbers of electrons available for bonding (called valence electrons). That gives the elements different properties and gets them neatly organized into the periodic table. Bonds can be single, double or triple, depending on how many pairs of electrons the atoms share. Different bonds have different strength (energy needed to break them) and length.

Bonds also determine shape of molecules. In the ethene image above, note how the two electron clouds keep the shape stable: the two “carbon + 2 hydrogens” parts cannot freely rotate, but are locked into one plane. This is extremely important! This is how complex structures like the DNA helix or proteins hold together, without collapsing.

Non-covalent bonds

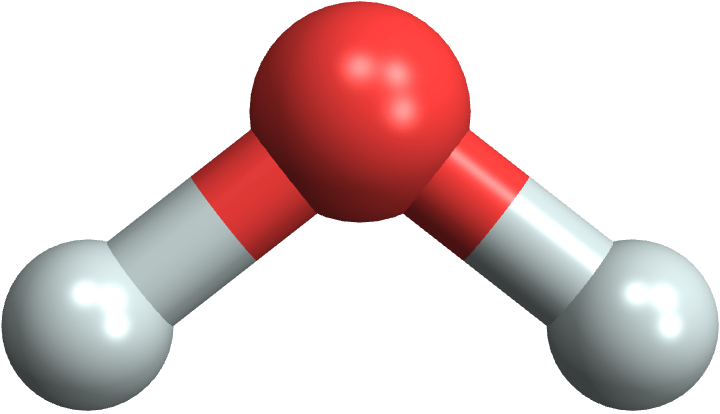

Look at the water molecule (H2O) and note that it’s asymmetrical:

MoleculePlot3D["water"]What that means is that the centers of the + charge (from protons) and the – charge (from electrons) are not at the same place, but will be slightly apart. That makes the water molecule polar — it’s like a little magnet now. That has many consequences: the molecules tend to hold together, which makes water liquid, and also makes many substances soluble in water.

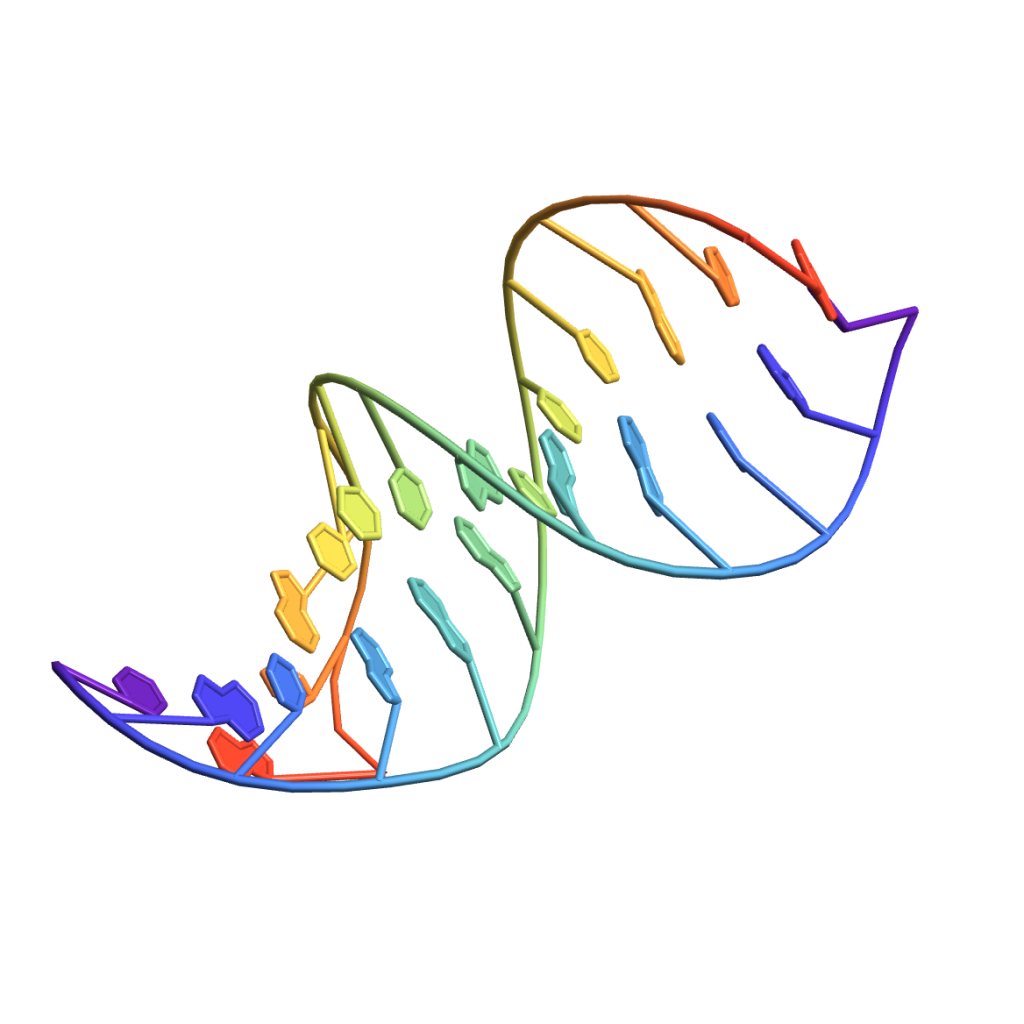

This weak “magnetic” attraction is called hydrogen bond. It’s order of magnitude weaker than the covalent bond. And you can see it in the double helix structure of DNA!

The two strands themselves are held together strongly by covalent bonds, but they are connected by a series of weak hydrogen bonds. That means we can separate them easily, and also the hydrogen bonds are very sensitive to the exact location of atoms in the “bases”. Only certain pairs of bases will “click” together. The bases are of four types (ACGT) and only the AT and GC pairs are compatible. That’s the principle for encoding information in DNA.

This moment is I think one of the pinnacles of the book: you can use the material you learned so far to suddenly understand something very complex and fundamental.

Building organic molecules

Now when we are sufficiently familiar with atoms and bonds we are ready to start building larger and larger organic molecules.

Hydrocarbons

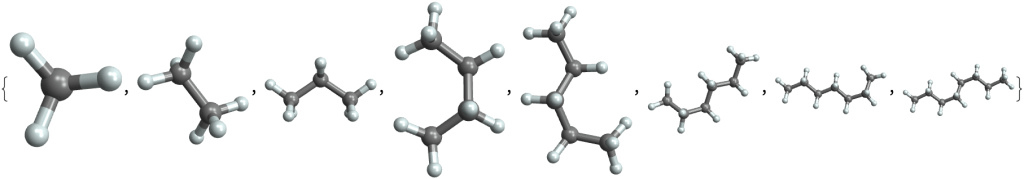

The simplest ones are hydrocarbons: chains of carbon atoms with attached hydrogens. Here are hydrocarbon molecules with chain lengths from 1 (methane) to 8 (octane):

MoleculePlot3D /@ {"methane", "ethane", "propane", "butane", "pentane", "hexane", "heptane", "octane"}They are so simple that they are useful mainly for burning. Fossil fuels are composed mainly from them. The shorter ones (methane, …) are in gas form, and are known as natural gas. Longer hydrocarbons (up to octane) are liquid and make up gasoline, used to power cars. Even longer hydrocarbons are called kerosene and are used by airplanes and rockets.

Functional groups

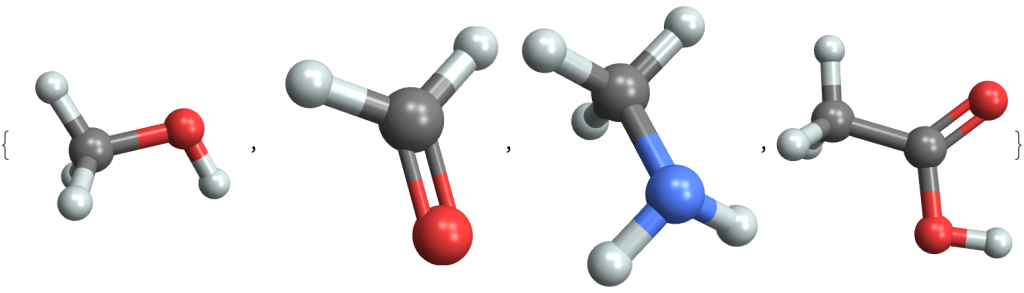

Hydrocarbons start to be more interesting when we replace the hydrogen atoms with other groups of atoms, called functional groups. Here are four molecules where a hydrogen is replaced with:

- an -OH group (called hydroxyl) to create an alcohol (methanol)

- an =O group to create an aldehyde (formaldehyde)

- an -NH2 group to create an amine (methylamine)

- a -COOH group to create an organic acid (acetic acid)

MoleculePlot3D /@ {"methanol", "formaldehyde", "methylamine", "acetic acid"}These functional groups react with each other in various ways, and can be combined to produce an infinite variety of organic compounds.

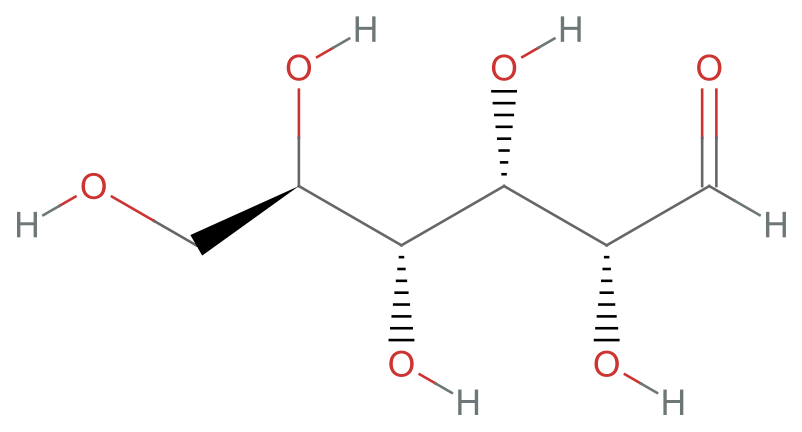

Consider glucose, which is a six carbon chain with five hydroxyl (-OH) groups and one aldehyde (=O) group:

MoleculePlot["glucose"]Amino acids

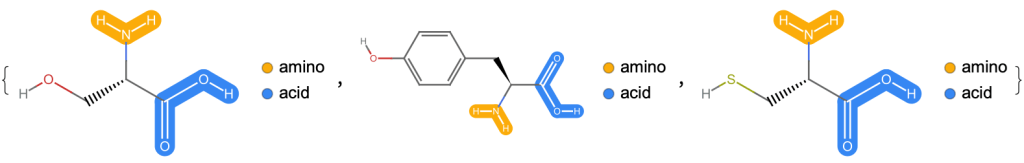

Now let’s have a look at three amino acids, serine, tyrosine and cysteine, and try to decode them. There are parts that they have all in common: it’s the -NH2 (amino) group and the -COOH (carboxyl) group next to it. The remaining parts are called “side chains” and are different. Some of them, like tyrosine, even contain elements like sulfur.

MoleculePlot[#, highlight]& /@ {"serine", "tyrosine", "cysteine"}Theoretically there are infinitely many amino acids, but in nature there are approximately 500 of them, and for human life 22 of them are essential.

What is interesting about amino acids is that the common parts (the amino and the acid one) can bond together to form so called peptide bond, and can form long chains, called proteins. Depending on which amino acids exactly you bind in what order, a very rich structure emerges, supporting life.

Proteins

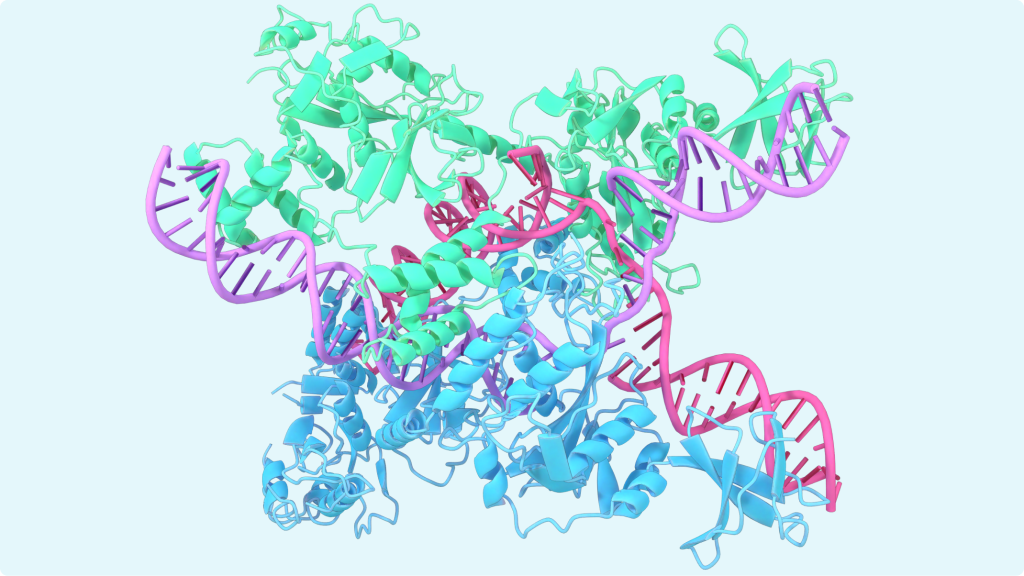

If you read recent news about AlphaFold, you often see pretty images like this:

What is that? These are various secondary structures created by long amino acid chains. Sometimes they fold into a helix like structures called α-helixes. You can see them colored in blue and green. You an also see flat zig-zag structures called β-sheets. And nowadays AI is helping us to predict how exactly will the amino acids chains fold and what large-scale 3D structures they will create.

This is I think the second pinnacle of the book. Putting it all together and understand such a complex structure like a protein.

Reactions

Now there are reactions: molecules interact together to form larger molecules, or to divide into smaller ones, replace one part by another.

After going through various types of reactions, you’ll be able to understand glycolysis: how glucose is broken down in your body and how energy is extracted from it. The energy is stored in molecules called ATP and then transferred in the cell to the place where the energy is released and consumed.

A very funny part of that is the ATP syntase molecule. It’s a thing that rotates, powered by protons flowing through a small turbine, and the working rotating part is a small robot that grabs an ADP molecule (adenosine di-phosphate), bends it a little, so that an extra phosphate group can easily attach, and produce adenosine tri-phosphate: ATP.

Chemical analysis

All the molecules and bonds look very simple, like a magnetic toy for kids, but they are all very small and invisible. We only know about them in a very indirect way. Observing how radiation is reflecting and scattering on them, how they behave in electric or magnetic field, how fast they travel in various mediums. The last chapter describes in detail various analytical methods. And it will make you want to buy a $50,000 HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography) machine from Agilent.

You must be logged in to post a comment.